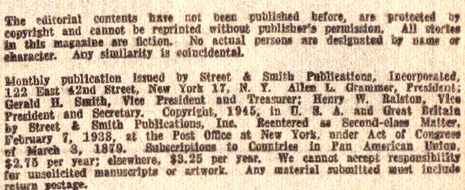

TOKYO, restless since the token bombing by General Doolittle, is quiet in the hour before dawn. Reports have come from the battle fronts that all Chinese "Shangri Las" are occupied or out of action, and the Navy has proved to every Nip's satisfaction that no American carriers are within raiding distance. Roof watchers and air-raid wardens are asleep at their posts.

Suddenly, from out of nowhere; comes flight after flight of bombing planes. Watchers awake, regard them complacently. When they see that they wear a star and not a circle on their underwings, it is already too late. Tokyo is being bombed again!

Headquarters takes it grimly. Somehow, the Yanks have managed to get through, but these planes can have little gas to reach friendly bases, will surely be shot down or forced down for want of fuel. Damaging though it may be, it is no more than another token raid.

But before the sun is high in the heavens, before the rubble of the first raid has stopped smoking, the bombers are back—this time from a different direction.

Headquarters is no longer calm, for the mysterious planes apparently vanished into the skies after the first raid.

Panic Grips the Flimsy City

The second raid, coming so rapidly on top of the first one, is far more serious. New fires are started, prove too much for an already overworked fire department. Water mains burst, power fails, factories are razed and flimsy wood and paper dwellings burn like the tinder they are.

All available fighter plane protection has long since been despatched in an effort to locate the bases from which the first raid was launched. A few bombers are shot down in flames, but not even Japanese torture can get information from men already dead or unconscious from wounds and burns.

After this second raid, panic grips the great city. Streets and avenues become congested with fleeing sons of the Mikado, making control of fires even more difficult. The smoke of burning Tokyo forms a perfect screen for another low-flying attack.

This attack, headquarters assures the populace, will not come. It can't. No aircraft carriers have been spotted, and the bombers, judging from the few that have been shot down, are not long-range jobs. And there is no such concentration of American medium bombers in China within striking range. It is a freak, they insist, like the Doolittle raid.

Wave on Wave, They Come Roaring

But the instinct of the people proves more correct than the generals' calculations. For, in the late afternoon, American bombers come roaring through the smoke for a third time and from a third direction. And in their wake, Tokyo suffers the greatest destruction that has visited it since the great earthquake and fire of 1923.

Fantastic? Sure it is. But so are the achievements and claims of Henry Kaiser, the wizard producer of the Boulder Dam and the Grand Coulee, whose shipyards are turning out prefabricated cargo vessels faster than the Germans can build torpedoes to sink them, the man who has promised delivery of 140-ton planes within a year.

So is North American's "Flying Wing," a mechanical pterodactyl if ever there was one. So is Igor Sikorsky's new helicopter, which can hover a few feet off the ground without moving forward or backward.

Where would these planes come from? Why, from the sky, naturally. And there're some things even more fantastic about that than the idea itself. In the first place, we have already successfully built and flown flying carriers. In the second place, only we can build them. And in the third place, we discarded the idea almost a decade ago for no other reason than that a depression-ridden Congress thought it a foolish waste of money.

The Value of Dirigibles

When the great dirigible Macon crashed in 1935, it meant the end of the American program in lighter-than-air ships. Preceded by the wrecks of the Shenandoah in 1924, and the Akron in 1933, other American-built airships, and followed two years later by the explosion of the great German air liner Hindenburg at Lakehurst, the disaster put the whole matter of dirigibles on the shelf.

Even the cheap and utilitarian blimp suffered. Two years ago, immediately before the outbreak of war with the Axis, America had exactly one modern blimp. Supplementing it were a few obsolete World War One models, two discarded Army non-rigids and two used Goodyear Trainers. In fact, the Goodyear Rubber Company itself had more blimps than our armed services.

An analysis of the various dirigible disasters reveals that in themselves these misfortunes should not have affected the continuance of a balloon program, especially in the light of subsequent world events. For the value of dirigibles in war has been proved again and again.

In 1918, the Allies feared the Zeppelins, and rightly so, far more than they feared Fokker fighter or Rumpler bomber planes. Great fleets of the German airships had bombed London and Paris almost from the start of the first World War. They covered incredible distances for those days, stayed aloft for amazing lengths of time, survived all sorts of weather and plane opposition.

Dreadnaught of the Air

The Zeppelin was, in effect, the dreadnaught of the air. With it, supplies were flown from Frederickshafen to hard-pressed German forces in East Africa, prolonging the war in the Dark Continent until 1917. It was, perhaps, the greatest all-German single weapon of the conflict.

And even those primitive gas bags were hard to shoot down. More than once, Zeppelins got safely back to their bases with thousands of bullet and shell holes in them and one-third of their hydrogen lost—and this despite the fact that hydrogen itself is one of the most explosive of elements. They had an amazing "lift" that left attacking planes far below them, and they mounted many guns on steady platforms.

At the time of the Armistice, Germany had just completed a super- Zeppelin designed for the express purpose of bombing New York. Billy Mitchell knew about it, was fully aware of the value of lighter-than-air craft as a weapon real and potential, and decided to get it for America.

A Great American Dreamer

He found some money lying around loose, secretly assembled and trained an airship crew.

His idea was to take them to Germany, buy the big ship and fly it back to this country. But before he could get under way, the French grabbed the prize, renamed it the Dixmude and proceeded to bring it down in the middle of the Mediterranean a few years later.

But Mitchell, determined that America should take the lead in airships, didn't give up. Largely at his insistence, a clause was written into the peace treaty compelling the Germans to build us the (at that time) biggest dirigible ever constructed.

At the same time, contracts were let out for Goodyear to build the Shenandoah, our first big rigid airship.

The Shenandoah, as every one knows, was split in two by an Ohio cyclone and wrecked with the loss of its commander, Zachary Landsdowne, and most of the crew. But among the survivors was Lieutenant Commander Charles Emery Rosendahl, and he took over and carried on with the work.

The Germans completed their airship, the ZR-2, and it was flown to America, where it performed invaluable service as the Los Angeles. It was finally, thanks to a peace-minded government, dismantled at Lakehurst in 1929.

Meanwhile, the United States Navy was going ahead on its own. They had Goodyear build the Akron and the Macon—ships more than twice the size of the Los Angeles. And each of these mighty dirigibles carried two planes.

Lessons from Disasters

A simple launching device was installed as well as a hook that enabled the planes to return to their air-borne hangars when their flights were completed. More than 3,000 launching and mid-air hookups were performed aboard these two aerial giants.

Both of these ships crashed under storm conditions which, putting unexpected stress on the great gas bags, caused their light framework to buckle. But out of each of these disasters, lessons were learned which obviate the recurrence of any similar catastrophes in airships of the future.

More important, neither of them caught fire. For they were filled with non-inflammable helium, of which only America has sufficient deposits for any airship program.

Where Germany has had to forfeit all of its vast experience and "know-how" in dirigible building and flying because it has almost none of this precious element, it is reliably estimated that about 1,000,000 cubic feet of helium a day is wasted with our natural gas deposits. We have literally helium to burn—except that it won't burn.

A Weapon Strictly American

Since the dreadful lesson of the Hindenburg, last of the German dirigibles, which burned at Lakehurst because of static electricity, it is plainly evident that shortage of helium, and that alone, has kept Adolf Hitler from constructing Zeppelins that could carry his blitz further in both distance and frightfulness than the Luftwaffe has been able to do.

Thus the dirigible, if it is to be used at all in this war, will be an American weapon. Six airships capable of carrying bombers will, according to Commander Rosendahl, who has been tragically reassigned to sea duty for the fourth time, although he is the world's greatest living balloon man, cost approximately as much as one of the eighty cruisers we are now building.

"They can travel twice as fast as a destroyer—eighty-plus miles an hour," he says, "and six of them can mother as many planes as one surface carrier. They use fewer strategic materials than anything else that flies or floats. Cotton cloth constitutes the bulk of an airship. A dirigible carries a smaller crew than a destroyer, can cruise for a week without refueling."

Imagine the effect of a raid of bombers launched from air bases on Berlin or Vienna as well as Tokyo. In the first place, since they would not have to go more than a few hundred miles at most, the planes themselves could sacrifice fuel for bomb loads.

From Nowhere and Return

They could strike from nowhere and return to nowhere, leaving ruin in their wake. They could reload and return again and again from a base that was always in motion far above the earth.

If a dirigible were shot down, planes could return to another one, some of whose bombers were missing. It would be a savage and indescribably effective blow at the heart of the Axis.

The scoffers, of course, never fail to bring up the matter of dirigible vulnerability. The answer to this is, "So what?"

Aircraft carriers at sea have already proved themselves tragically vulnerable to all sorts of attack, and sufficient dirigibles to carry four to six times as many planes as the largest sea-borne carrier could be built for the same cost in a fraction of the time and would offer a vastly more dispersed and elusive target.

Then, too, the dirigible is not as vulnerable as scoffers pretend. In the first place, the defenders have got to find it. It can operate as a mother ship a hundred or more miles from the target in any direction, can lurk above cloud banks, using a cable-drawn observation car at intervals if astral navigation proves insufficient, and can keep constantly on the move.

A Deadly Weapon—Our Own!

It still has the defensive possibility it had in the last war—the ability to rise vertically and more swiftly than any interceptor, and a steady platform for Bofors or anti-aircraft machine-guns. To these is added not only the strength of non-inflammable helium, but the protection of its own fighter planes. If Flying Fortresses can shoot their way through plane attacks, why not dirigibles?

In quantity, such airships would be unanswerable—if our ground and plane-minded leaders can see the light. There is, of course, a distinct possibility that they already have. The need for the blimp, which has proved an invaluable anti-submarine and convoy protection instrument, was recognized in 1940 when Congress appropriated money for forty-eight of the hardy non-rigid ships, most of which are already in service.

This appropriation, however, was followed by the passage of a bill to construct 200 lighter-than-air craft—and provisions for dirigibles were at last included! America may well be on the way to employing this deadly weapon it alone can operate.

Click to join 3rdReichStudies

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Fair Use Notice: The Propagander!™ may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Sources: Two superior Yahoo! Groups, magazinearchive and pulpscans, are the original sources for the scans on this page. These Groups have a number of members who generously scan and post rare and scarce magazine and pulp scans for no personal gain. They do so for love of the material and to advance appreciation for these valuable resources. These Groups are accepting new members; join now!